will students get smarter or stop thinking?

will students get smarter or stop thinking?

When students entered Tsinghua University in Beijing this year, one of the first representatives they met wasn’t a person. Admission letters to the prestigious institution came with an invitation code to an artificial-intelligence agent. The bot is designed to answer students’ questions about courses, clubs and life on campus.

The future of universities

At Ohio State University in Columbus, students this year will take compulsory AI classes as part of an initiative to ensure that all of them are ‘AI fluent’ by the time they graduate. And at the University of Sydney, Australia, students will take traditional, in-person tests to prove that they have learnt the required skills and not outsourced them to AI.

All this is part of a sea change sweeping through campuses as universities and students scramble to adapt to the use of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT. These tools can, within seconds, analyse complex information, answer questions and generate polished essays — some of the exact skills that universities have conventionally taught. Eighty-six per cent of university students were regularly using AI in their studies in 2024, according to one global survey1 — and some polls show even more. “We are seeing students become power users of these tools,” says Marc Watkins, a researcher who specializes in AI and education at the University of Mississippi in Oxford.

To some, AI presents an exciting opportunity to improve education and prepare students for a rapidly changing world. Universities such as Tsinghua and Ohio State are already weaving AI into their teaching — and some studies hint that AI-powered tools can help students to learn. A randomized controlled trial2 involving physics undergraduates at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, suggested that those who used a custom-built AI tutor learnt more in less time than did students who were taught by humans alone.

But many education specialists are deeply concerned about the explosion of AI on campuses: they fear that AI tools are impeding learning because they’re so new that teachers and students are struggling to use them well. Faculty members also worry that students are using AI to short-cut their way through assignments and tests, and some research3 hints that offloading mental work in this way can stifle independent, critical thought.

Universities must move with the times: how six scholars tackle AI, mental health and more

And some academics are angry that universities are allowing or even encouraging the use of AI tools — many of which are controlled by companies, have unknown cognitive impacts and are dogged by ethical and environmental concerns. An open letter released in June by scholars objecting to the uncritical adoption of AI technologies by universities quickly racked up more than 1,000 signatures from academics worldwide (see go.nature.com/4qpkygs). “Our funding must not be misspent on profit-making companies, which offer little in return and actively de-skill our students,” it reads.

There is one point of agreement among both enthusiasts and sceptics: the future has already arrived. “The rate of adoption of various generative AI tools by students and faculty across the world has been accelerating too fast for institutional policies, pedagogies and ethics to keep up,” says Shafika Isaacs, chief of section for technology and AI in education at the United Nations cultural organization UNESCO, in Paris.

The AI generation

Universities have been adapting to new technologies for decades — from computers and the Internet to online courses. But generative AI tools present a fundamental challenge, researchers say. Not only can they quickly perform some of the core tasks that universities teach students, but they have spread and are changing at pace. “The thing that is different about AI to every other technology is the speed at which it moves,” says Sue Attewell, head of AI at Jisc, a non-profit digital and data body for UK higher education, headquartered in Bristol.

Surveys around the world show that students are quickly incorporating AI into their lives. “The number of users who are essentially young teens is just astronomically high,” says Watkins. “You’re talking hundreds of millions of users worldwide below the age of 24.” And science students seem to be early adopters. This year, the AI firm Anthropic, in San Francisco, California, analysed one million anonymized conversations between university students and its generative AI, Claude. It found that students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics were using it disproportionately more than were those in areas such as business and humanities4.

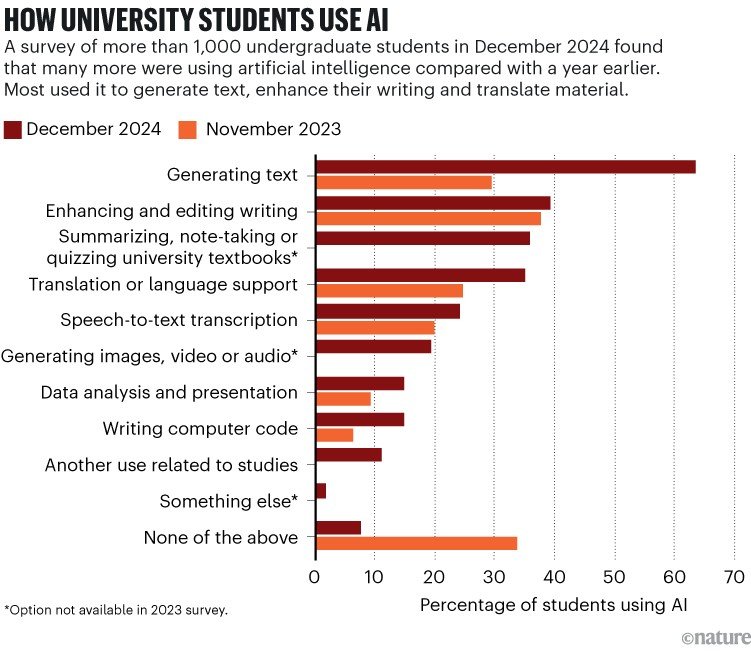

But what are students using AI for? In a survey of more than 1,000 UK students by the Higher Education Policy Institute, a think tank in Oxford, UK, most were, unsurprisingly, using AI tools to write, improve or summarize text (see ‘How university students use AI’). Nearly 90% of students said they had used generative AI for assessments such as exams or coursework. Most (58%) said they used it to explain concepts in the assessment, 25% used AI-generated text after editing it first and 8% admitted they’d used raw AI-written text5.

Source: J. Freeman Student Generative AI Survey 2025 (HEPI, 2025)

Attewell, who has conducted student focus groups on AI, says many students are using the tools to streamline their studies and become more efficient, not to cheat. And many just want guidance on how to boost their learning with AI, she says. Students might “know how to use (AI) brilliantly on social media or for their social life, but it doesn’t mean that they know how to use it for academic use”.

This, however, is where many universities are falling short. Institutions around the world have been scrambling to introduce policies for staff and students on the best ways to use AI — but with mixed results. On US campuses, “it’s been chaotic for the past two and a half years, and I don’t think it’s going to change anytime soon,” Watkins says. That’s because many institutions allow individual faculty members to decide whether and how AI can be used in their courses, he says, which leaves some students confused. “We might have a freshman student taking five classes, and they will be exposed to five different AI policies.”

In Australia, by contrast, there has been a strong, nationally coordinated response, educators say, in part because the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency has worked to develop guidelines with universities since 2023. And in China, “the integration of AI into universities is not optional, but an integral part of national strategy,” says Ronghuai Huang, co-dean of the Smart Learning Institute at Beijing Normal University.

Data and anecdote suggest that faculty members are embracing AI more cautiously than students are. Some staff are using AI tools to automate their own work, such as by helping to draft feedback on assignments, say researchers, whereas others are rejecting it outright. A survey this year of more than 1,600 faculty members from 28 countries by the Digital Education Council, an organization focused on technology in higher education, found that around 60% were using AI tools in teaching — less than the proportion of students using them6. However, 80% said their institution had not made it clear how to use AI in their teaching. “Faculty use is less sophisticated than student use,” says George Siemens, who studies technology and education at the University of South Australia in Adelaide.

Meanwhile, big technology companies such as OpenAI and Google have been pitching their products to students and universities. “We’re inundated by companies wanting to partner with us,” says Ravi Bellamkonda, Ohio State University’s executive vice-president and provost. Last year, OpenAI introduced ChatGPT Edu, a version of the popular chatbot tailored for universities. This February, when the California State University system announced it was giving its 520,000 students and faculty members access to that tool, it became “the largest implementation of ChatGPT by any single organization or company anywhere in the world”, according to OpenAI. In August, Google announced it was making its most advanced AI tools available for free to students aged over 18 in the United States and in a handful of other countries.

Education specialists say that tech firms are motivated by commercial interests and the opportunity to embed their AI systems into the lives of millions of young users. Universities that strike agreements with tech firms typically get campus-wide access to the latest AI models and data protection, meaning that student and faculty data and academic work are not fed into an AI training model.

Some universities are grabbing the AI bull by the horns. Danny Liu, a biologist who specializes in educational technology at the University of Sydney, was one of the first to develop a generative AI platform tailored to higher education. Called Cogniti and developed in 2023, it is now embedded in the university’s digital learning platform and allows teachers to design custom AI agents for their courses. This might be an AI tutor for a science module, or an AI tool that expands brief marking comments into more specific student feedback. Cogniti is being used by more than 1,000 educators at his university, Liu says, and has been shared with more than 100 universities worldwide.

The great university shake-up: four charts show how global higher education is changing

At Tsinghua University, academics also quickly started experimenting with ChatGPT after its release in November 2022, says Shuaiguo Wang, who directs the Center for Online Education there. Within a year, about 100 different AI teaching assistants had sprung up, and the university sought a more systematic approach. It also didn’t want to be reliant on any one AI model — such as the large language models (LLMs) that underlie ChatGPT and related tools — because “a new model emerges almost every day”, Wang says. Another key goal was to correct hallucinations, the inaccurate content that LLMs sometimes spout.

In April last year, the university led the development of a central, three-layer ‘architecture’ to incorporate AI into teaching. The bottom layer is where AI models are plugged in: the system draws on about 30 models from companies including DeepSeek, Alibaba Cloud, OpenAI and Google, Wang says. The middle layer contains ‘knowledge engines’ that hold accurate, up-to-date information for different academic fields. The top layer consists of various student-facing platforms, including an educational one that hosts teaching assistants, as well as the AI bot to help students starting at Tsinghua.

As part of this system, for instance, students can review slides after a class and click a button saying ‘I’m confused’. This allows them to ask a pop-up AI agent questions. The intermediary layer analyses the question and directs it to the appropriate AI model, as well as searching its own databases; it then compiles the information to provide an accurate answer. Wang says the system has been adopted by hundreds of universities across China.

This year, Wang is changing tack and launching studies to ask a crucial and outstanding question: do students using AI tools actually learn more? Early results — as yet unpublished — have raised some red flags. Wang and his colleagues found that students who use an AI tutor often score higher in tests immediately after a class than do those who don’t use the agent. But two to three weeks later, the AI users scored lower than their peers. “Students might have a false sense of understanding,” he says.

Classroom concerns

Wang is not the only one worried about the impact of AI on students’ learning — as Nataliya Kosmyna discovered when, in June, she and her colleagues released a preprint7 suggesting that students who use ChatGPT to help write an essay use less of their brains than do students who write it on their own. She has since received some 4,000 e-mails from school and university teachers worldwide who are concerned that the result reflects what is happening to students in their classrooms who are using AI. In a lot of cases, “they actually sound very desperate”, she says.

Kosmyna, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and her team used electro-encephalography (EEG) to study the patterns of electrical activity in 54 students’ brains as they wrote 20-minute essays on questions such as “Do works of art have the power to change people’s lives?” The students were split into three groups: one with access to an LLM; another that could use websites and search engines but not LLMs; and a third that relied only on their own knowledge. The team used EEG to measure ‘connectivity’ between brain regions — the extent to which areas were communicating with each other.

Students using only their brains showed the strongest and widest pattern of connectivity and were usually able to later recall what they’d written. The LLM-using group showed the weakest connectivity — suggesting that there was less cross-brain communication — and could sometimes barely remember a word of their prose.

Kosmyna acknowledges that the study involved only a small number of students and did not look at the long-term impacts of using AI, among other limitations. (She also found it ironic that some commentators misinterpreted the study because they used AI to generate incorrect summaries of her 200-page preprint.) But the study fuelled a widespread concern that students who rely on AI in their studies are failing to develop valuable skills such as critical thinking — the ability to analyse and critique information and to reach considered conclusions. Anthropic’s analysis of one million student–AI conversations in Claude showed that nearly half of them involved individuals seeking direct answers or content with little engagement on their part.

ChatGPT for students: learners find creative new uses for chatbots

Olivia Guest, a computational cognitive scientist at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands, who led the writing of the June protest letter, says she has observed related problems with students in the past couple of years. “Their skills have dramatically changed,” she says: some struggle to reference a source or write an essay.

نشر لأول مرة على: www.nature.com

تاريخ النشر: 2025-10-21 03:00:00

الكاتب: Helen Pearson

تنويه من موقع “yalebnan.org”:

تم جلب هذا المحتوى بشكل آلي من المصدر:

www.nature.com

بتاريخ: 2025-10-21 03:00:00.

الآراء والمعلومات الواردة في هذا المقال لا تعبر بالضرورة عن رأي موقع “yalebnan.org”، والمسؤولية الكاملة تقع على عاتق المصدر الأصلي.

ملاحظة: قد يتم استخدام الترجمة الآلية في بعض الأحيان لتوفير هذا المحتوى.